Body

When a man’s body is at ease and his spirit is recovered, he becomes One with heaven.

– Chuang Tzu

The path to enlightenment, as taught by the Center of Traditional Taoist Studies, requires a personal commitment to develop the entire being — beginning with the physical self. Contentment — which is the goal of enlightenment — is nearly impossible without a healthy body. Accordingly, the early masters of Taoism created an integrated program whose first priority was physical development. The Taoist science of Qi (Chi) gave birth to the practice of Qi Gong (Chi Quong). Qigong is a rigorous exercise program that not only builds the body’s channels for Qi but also regulates the flow of Qi through them. Consistent with Taoism’s recognition of the mind/body link, there are both physical and mental Qigong exercises or, more traditionally labeled, internal and external Qigong. A Westerner would likely find that physical Qigong resembles the early morning Tai Chi (taiji) exercises performed by Chinese practitioners in parks throughout the world. Mental Qigong is known as “meditation” in the West.

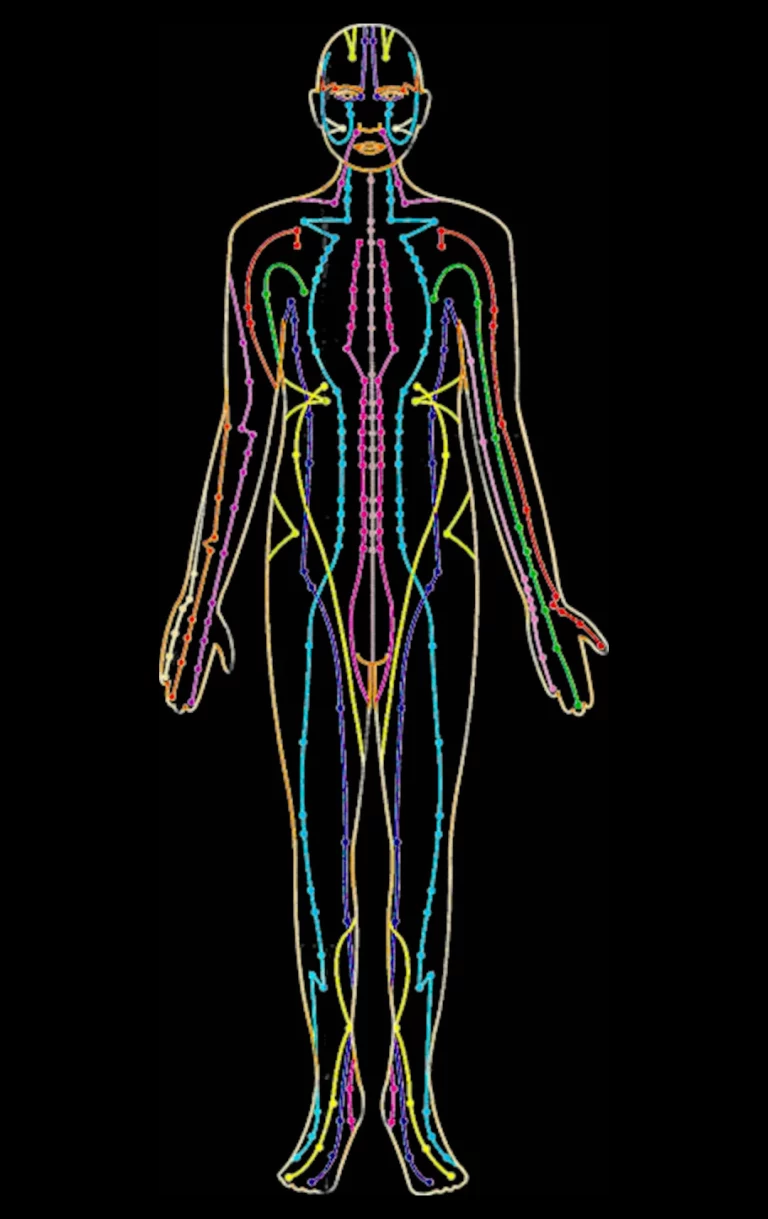

Physical Qigong’s mastery of body and mind requires focus and concentration, thus teaching the practitioner how to control thoughts and actions. In doing so, he also learns to manage individual desires — the prerequisite for spirituality. It is a Taoist tenet that an individual undisciplined in the physical realm can never be spiritual. Thus, physical Qigong is a practical step towards achieving a spiritual state. Said another way, if the body is the “house” of the soul, it must be in good condition lest broken windows make it functionless for the spirit. Physical Qigong’s primary goal is flexibility, the best indicator of youthful chi. And in the Taoist formulation, flexibility yields longevity. Qigong’s second goal is to improve sensitivity. By feeling the body move through hundreds of prescribed motions, the practitioner becomes sensitive to the signals it emits. Consequently, he can detect any malfunction — whether illness or injury — in their early stages, allowing for prompt treatment. Physical Qigong develops the body’s invisible channels of Qi, which are arranged in a configuration called the “meridian system”. Diagrammed, the human meridian system resembles the circulatory system, as it is comprised of pathways that roughly follow the arteries and veins throughout the body. In essence, blood can be thought of as the “life force” of the visible world, while Qi is the “life force” of the unseen world.

Physical Qigong

He can sit still like a corpse or spring into action, like a dragon

– Chuang Tzu

Physical Qigong exercises use various positions and movements to direct chi in precise ways. For example, one of the most basic Qigong positions is the “horse stance”, whereby a relatively wide-legged, low hipped position — resembling the posture of a man astride a horse — directs Qi in a spiral pattern into the male’s prostate region. This area is susceptible to disease, particularly for the older male, and remains untouched by Western exercises. Physical Qigong simply and elegantly helps prevent such illnesses.

Qigong’s positions must be exact, for even a slightest change in the angle of hands or feet, can dramatically affect the Qi’s flow along the various meridian channels. For this reason, Qigong is always taught under close supervision at the Center of Traditional Taoist Studies. As the practitioner becomes more proficient, new subtleties are added to make the exercises more powerful and effective. There are different levels of Qigong — ranging from “sitting” Qigong for infirmed patients, increasing in difficulty to intense Qigong for professional athletes.

Physical Qigong synchronizes its movements with breathing. The deeper the breathing, the greater the volume of Qi pushed through the meridian system. Simply stated, the body’s position during Qigong controls the direction of Qi flow while the depth of synchronized breathing controls the volume of chi flow. Such deep breathing yields powerful results, but can be dangerous if misused. Shallow, natural breathing during Qigong accelerates low volumes of Qi, so any misdirection is of little consequence. Uncoordinated deep breathing, however, is dangerous, reinforcing the requirement for Qigong’s close supervision at the Center.

While the mechanical aspects of Qi development are logical, predictable and often in sync with Western medical theory, there is a deeper, more profound aspect to physical Qigong. As discussed earlier, one goal of the Taoist is to synchronize himself with universal energy. In essence, the Taoist is a conductor of Qi between the heavens (Cosmic Qi) and earth (grounded, organic Qi), striving to improve Qi flow rotating from heaven to earth and back. By opening the body’s channels, physical Qigong makes the Taoist more receptive to cosmic Qi. Taoists recognize that the healthful characteristics of youth — not its outward appearance — are critical to a content existence. Since our minds and souls are saddled with a physical form during their short stay on earth, a healthy body is a prerequisite for contentment. The various characteristics of youth — flexibility, sound joints, and strong muscles — are, therefore, treasured “possessions”. Thus, physical Qigong is truly the Taoist “fountain of youth”, performing remarkable feats in transforming the body into a stronger, more flexible, and healthier vessel. Some speculate that its amazing efficacy from ancient times is testament to mystical origins. Regardless of its source, however, physical Qigong is an important, practical application of Lao Tzu’s principles taught at the Center for Traditional Taoist Studies.